|

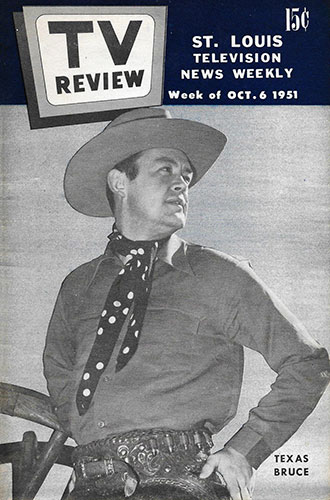

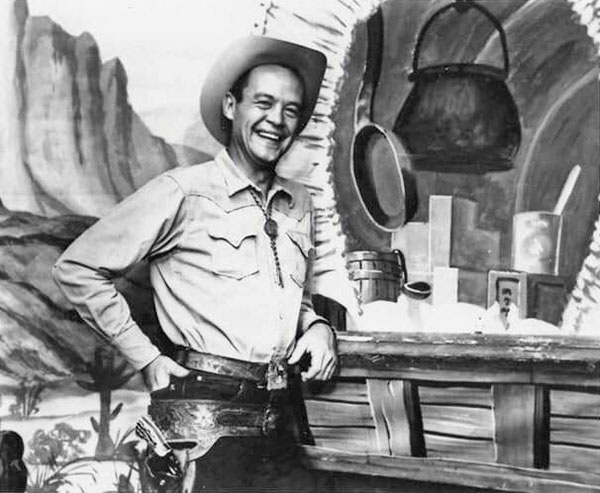

Texas Bruce

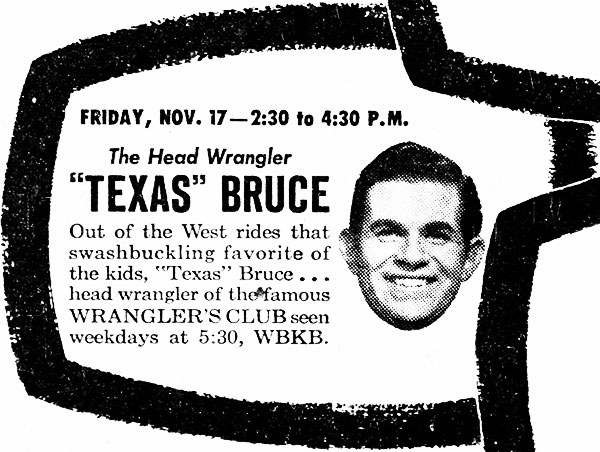

The Wrangler's Club aired on Chicago television from 1949 to 1951. Chicago born Bruce Roberts hosted the show as "Texas" Bruce Roberts. Dressed in western garb, Roberts played the guitar and told western stories in between segments of western films.

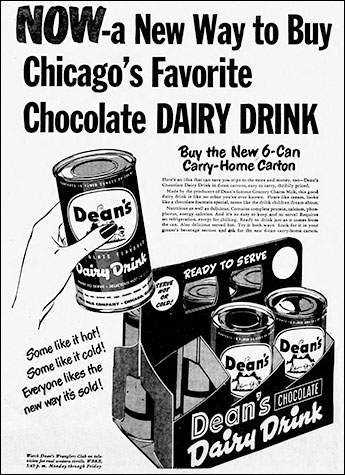

The program, only 15 minutes in length and

geared toward youngsters, was sponsored by Dean's Dairy and branded

Dean's Wrangler's Club. When Dean's began marketing a chocolate

drink product in the late 1940s, the company branched out to

St. Louis.

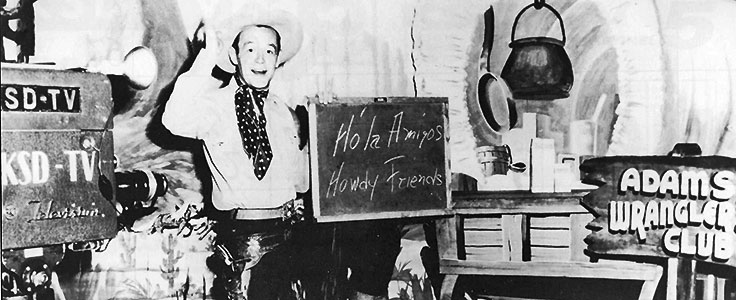

Dean's Chocolate Dairy Drink arrived on St. Louis grocery shelves in 1949. To help market their product, Dean approached KSD-TV about bringing their successful Wrangler's Club from Chicago to St. Louis. KSD-TV, which had only been broadcasting since 1947 and was hungry for local content, brought the Wrangler's Club to their airway on March 6, 1950. And since Dean already had the marketing materials, "Texas Bruce" was the show's host.

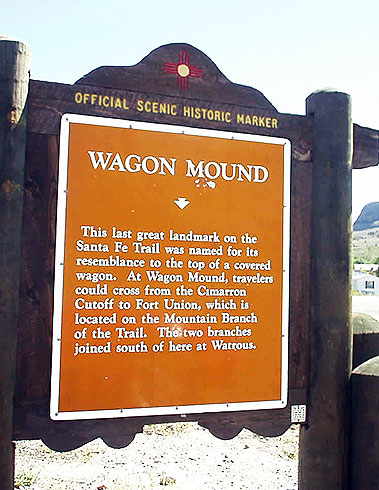

Harry Cochran Gibbs was born on March 21, 1917 in Wagon Mound, New Mexico. His father, a physician, had moved with Gibbs' sister and mother from Colorado by train, stagecoach and buckboard. Among his earliest memories were cattle drives through Wagon Mound's main thoroughfare, with his mother standing guard at the fence to prevent steers from breaking through and trampling her flowers.

Gibbs started riding the neighbors' calves,

then transferred to his mother's cow. By the time he was four, he

was riding a horse. When he was five, the family moved to Las Vegas,

New Mexico, a town 45 miles south of Wagon Mound, where there were

schools for Gibbs and his sister.

Gibbs finished high school at Las Vegas, and then worked on ranches and chased cattle as a cowboy. He loved the freedom and vigor of the work, but forty dollars per month, plus room and board, didn't seem to offer much of a future. Gibbs made his way to St. Louis and entered Washington University, intending to study medicine. But the stage bug struck him and he never recovered.

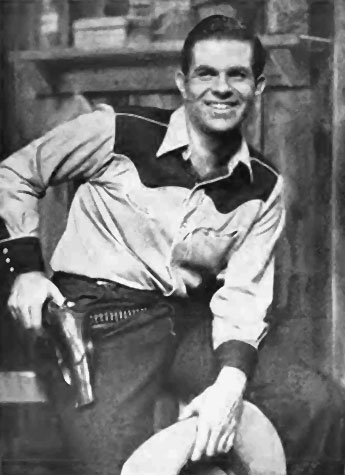

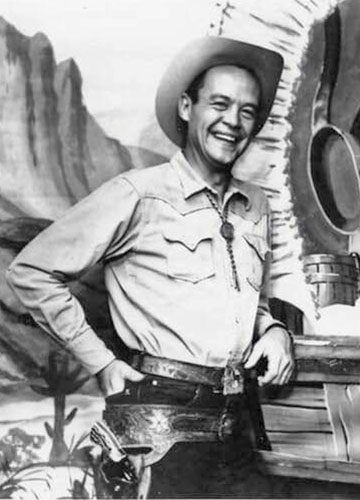

His first role was a cow-puncher in a play produced by Thyrsus, the Washington University drama society. Gibbs went on to win the Wilson Award for Acting, the highest honor at the university in the theater field. During one production he met another student, Jean Fisher, who he would marry. While in school, Gibbs worked as a laborer in a steel mill, punched cattle in New Mexico, directed drama projects, played stock in Michigan and worked with the Hollywood Community Theater. He graduated with a degree in dramatic art in 1941, six years after he started. Gibbs enlisted in the Marines upon graduation and emerged in 1946 as a major. Back in St Louis, he free-lanced as actor, narrator, disc jockey or whatever was needed at virtually every radio station in town. When KSD-TV began operation in 1947, Gibbs immediately got onboard, appearing with Dottye Bennett in a quiz show sponsored by Union Electric. And when KSD premiered Dean Dairy's Wrangler's Club in 1950, the cowboy from New Mexico was a natural to step in as the St. Louis Texas Bruce. * * * * *

The Wrangler's Club was initially broadcast Monday through Friday from 5:00 to 5:15,

following Howdy Doody. Gibbs, who was six feet two inches tall and

weighed 200 pounds, approached the wranglers with a disarming

semi-drawl which was part New Mexico and part Missouri. Outfitted in authentic

cowboy garb, from sombrero to boots, he glided through the

15-minute program, deceptively crammed with personal greetings to

his wranglers, western lore, plugs for undertakings by the Boy

Scouts, tips on the cattle business, a movie, the inside dope on

Indians, a Spanish lesson, advice on woodsmanship and rope tricks.

Gibbs ended the show in Spanish with his catchphrase, "Hasta la

vista, vaqueros."

Proper handling of a rope was a serious art with Gibbs. He started learning how to use a rope when he was two years old. He knew that catch-roping by youngsters could be dangerous.

Gibbs regarded the daily Spanish lesson he offered the wranglers as a genuinely educational part of his program.

Gibbs' Spanish was a concoction of Indian, Spanish, Mexican and English which he had to learn as a boy in New Mexico if he was going to have the maximum number of playmates. He called it border Spanish.

The western movie portion of the show, which was serialized throughout the week, was a cause of constant vigilance and concern, and had to be remodeled to conform to Wrangler's Club standards. Gibbs insisted on eliminating sequences which exhibited can-can girls, wanton killings and any suggestion that lawlessness led to any but a bad end. Gibbs' fan mail was enormous and a great deal of it was scrawled messages requesting personal recognition by Texas Bruce during the telecast. It snow-balled to such proportions that Gibbs had to make a choice between acceding to the demand or dropping most of the features of his program. As a gesture of appeasement, he opened an observation booth at KSD-TV studios, which was jammed with wranglers for each show. They generally attended in organized groups, such as Boy Scouts and Cub Packs. But not everyone was happy with Texas Bruce, or at least the way he promoted Dean's Chocolate Dairy Drink.

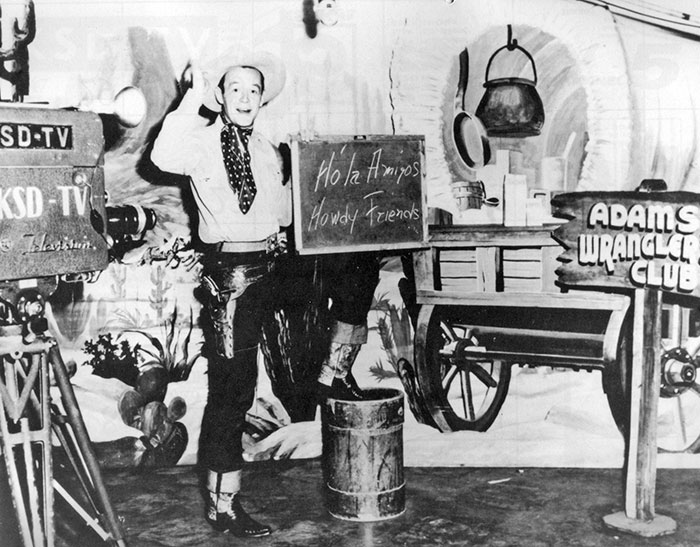

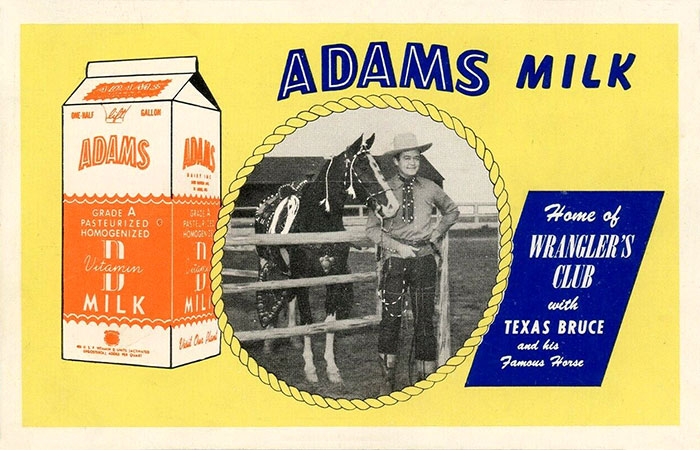

Within a year after the Wrangler's Club went on the air,

Dean's Dairy dropped its sponsorship and Adams Dairy acquired the property.

Gibbs had a full schedule of special

appearances for Scouts, Cubs and Brownies, parades and benefit

performances. For outdoor appearances, he was accompanied by his

horse Trusty, a five-gaited show animal.

In about 1953, a live studio audience was added to the Wrangler's Club. For the most part, they were the same organized groups that had filled the observation booth. But now, in addition to watching the show, they could interact with Texas Bruce.

At some point in the show, Gibbs would ask each

wrangler what they wanted to be when they grew up. Then they got to

say hello to their friends, often with the familiar refrain, "Hi,

Mom. Hi, Dad. Hi, everybody."

Legend has it that one afternoon a precocious member of the audience intoned his salutations to his mom, dad and everybody, and then pausing for dramatic effect, gave the universal middle-finger sign and said, "This is for you, Herbie!" Gibbs was asked about the incident many times over the years.

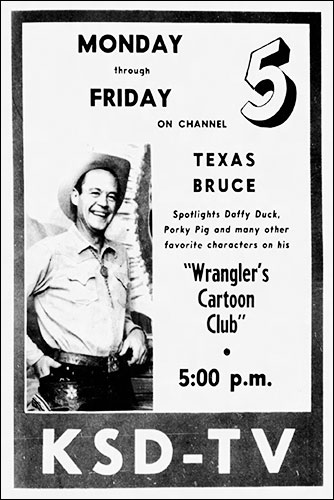

In 1955, the program was extended to a half hour and rebranded the "Wrangler's Cartoon Club." The western movie was replaced by Daffy Duck and Porky Pig. For a brief time in 1957, the Wrangler's Cartoon Club could be seen Monday thru Saturday. Little Lulu was added to the mix and the show was extended to 45 minutes, from 5:00 to 5:45.

In 1958, the Little Rascals began airing on the

show. The Our Gang series and Bozo the Clown were added in 1959. In

1959, wranglers at home could see Texas Bruce in color Ė if their

parents owned a color TV.

Gibbs was protective of his wranglers and concerned about the medium that broadcast his show.

What irritated Gibbs most were some of the products being sold on the show, especially the toys that promised to do things they didn't or couldn't do. He recalled a rocket that claimed to simulate a real launch. The suggestion was that kids could blast the rocket to Mars if they wanted.

Another toy, said to be unbreakable, broke into smithereens when it hit a concrete floor. Gibbs dropped it on the air to prove the claim was untrue. Strange things happened on the show. Things you'd expect from kids jammed into studio bleachers filled with ice cream and Twinkies.

Sometimes, when it was a beautiful day, Gibbs would suggest to the kids watching at home that they go play outside.

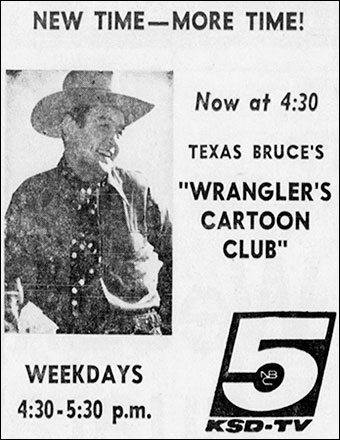

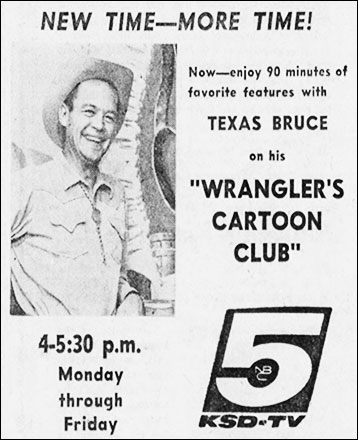

In 1960, the Wrangler's Cartoon Club had become

so popular the it was expanded to an hour, from 4:30 to 5:30. In

1961, it was expanded to 90 minutes. Wranglers had to wait from six

months to three years to attend the show.

Texas Bruce told his television audience "Hasta la vista, vaqueros" for the last time on January 25, 1963. Gibbs left the Wrangler's Club to take a position with Sunnen Products. Clif St. James (as Corky the Clown) would take over as host of the show.

* * * * * Gibbs' stay with Sunnen Products was short lived. Gibbs had begun working with an advertising agency in 1959, along with hosting the Wrangler's Club. By the beginning of 1964, he had returned to that agency. He worked in advertising for the next 20 years. After leaving the advertising business, Gibbs did freelance talent work as an actor and on radio. He also was active in many community groups. He lived with his wife in Webster Groves in the same house their four sons had grown up in. There wasn't a television set in that house for two years after Gibbs became Texas Bruce in 1950.

Gibbs was reluctant to ride again as Texas Bruce. He likened such a comeback to "desecrating your own grave."

Harry Gibbs said his final "Hasta la vista" on July 18, 2008. He passed away at the age of 91. His son David remembered watching his fatherís show with friends when he was a child.

Harry Gibbs had finished playing his part.

Texas Bruce lived on.

Copyright © 2022 LostSTL.com |