|

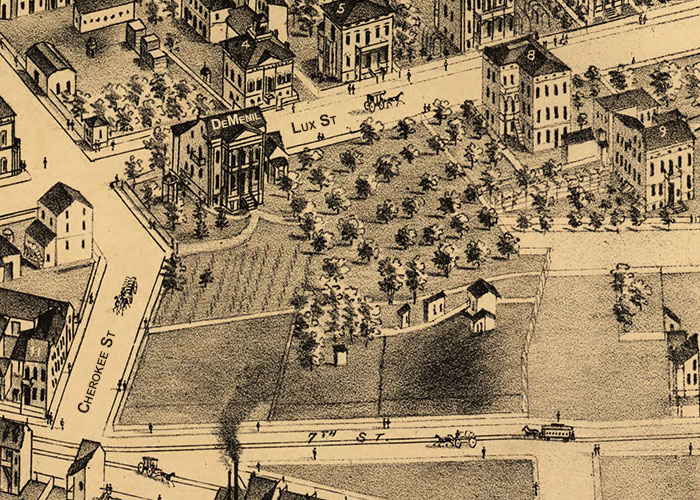

Cherokee Cave In 1865, Charles Fritschle leased land at the southwest corner of Seventh and Cave streets in St. Louis from Dr. Nicolas DeMenil. Fritschle and his partner, Louis Zepp, built a small brewery on the lot which they called Minnehaha. Nicolas DeMenil owned a mansion at the opposite end of the property, bordered by Lux and Cherokee streets. A sinkhole on DeMenil's property led to a cave, 50 feet below the surface. The Minnehaha Brewery enlarged the opening, created two additional holes in the cave’s ceiling for ice and beer casks, and leased the underground cavity for the storage and aging of their beer.

Unfortunately, the only outlet for Minnehaha's

beer was a saloon owned by Louis Zepp. The brewery failed in 1867,

and Nicolas DeMenil reclaimed his properties.

Nicolas DeMenil was born in France. He was

educated in medicine and pharmacy, as well as in science, history,

political economy, philosophy and general literature. As a

22-year-old lieutenant in the French Army, he arrived in St. Louis

in 1834 for a short visit. But his visit was extended indefinitely

when he met Emilie Sophie Chouteau, the daughter of Auguste Pierre

Chouteau and the great-granddaughter of Marie Therese Chouteau, the

first white woman to settle in St. Louis. They were married two

years later and had two children, a daughter, who died before her

first birthday, and a son, Alexander.

DeMenil was part owner in a chain of drugstores and became quite wealthy. In 1856, he and his business partner, Eugene Miltenberger, bought 5 acres of land outside the city limits, at Lux and Cherokee streets. On the grounds was a small farmhouse, which served as a country retreat for the two men's families. In 1861, Miltenberger sold his interest in the property to DeMenil. In 1861, DeMenil hired English architect Henry Pitcher to turn the farmhouse into a Greek Revival mansion. The most striking addition was front and back colonnaded porches with stately ionic columns. In 1863, the DeMenil family moved into the mansion full time. Two years later, Nicolas DeMenil leased the cave under his property to the Minnehaha Brewery for the storage and aging of their beer.

In 1876, DeMenil built a row of ten residences as rental property on the east side of his land.

Nicolas DeMenil died on July 9, 1882. His son Alexander inherited his father's mansion and property, and lived there until his death on Thanksgiving Day in 1928. Alexander left the property to his son George, who lived there for only one year. Caretakers lived in the house until George sold the property in 1945. * * * * * Lee Hess was born in St. Louis on May 28, 1900. He grew up in a well-to-do South St. Louis family; his father was president of the Chanute Zinc Company. At age 15, Hess was arrested with three other teenage boys for joy riding in stolen Ford automobiles. At age 18, he worked as a clerk at the Hudson Drug Company. At age 19, he was a shoe salesman. At age 29, Hess was indicted by a federal grand jury for bankruptcy fraud as treasurer of the bankrupt Anchor Lumber Company. The indictment was subsequently dropped. In 1927, Hess formed the Halitosine Company and became its president. The company's main product was Halitosine, an all purpose antiseptic mouthwash.

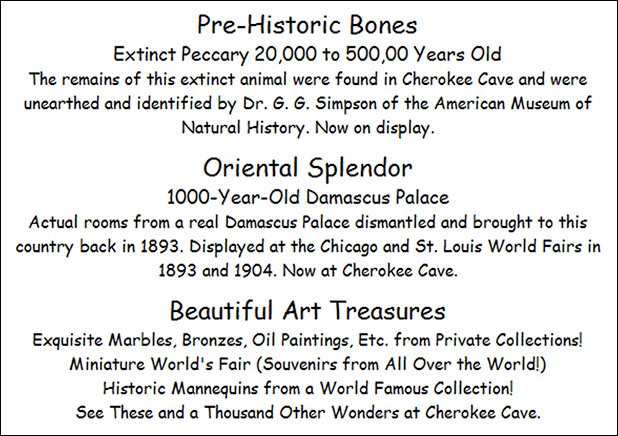

Halitosine proved to be a successful product and provided Hess with the funds to diversify into real estate. At a meeting of the St. Louis Drug Club in the early 1940s, Hess learned of the existence of the cave under the DeMenil property. He formed the Cherokee Realty Company and on March 2, 1945 purchased the DeMenil Mansion and property, including the ten row houses, from George DeMenil for $185,500. Lee Hess had more interest in what was beneath the DeMenil property than above. He planned to develop the underlying cave system into a night club or restaurant. But a fortuitous discovery made while the cave was being cleared of debris led Hess in a different direction. Within a year of his purchase, Hess engaged a crew to cut through an obstructed passageway within the cave. While clearing the passage of clay and stone debris, the crew discovered a large number of animal bones.

Two experts from the American Museum of Natural History in

New York City came to St. Louis to examine

the specimens. Most of the remains were of an

extinct form of the peccary, a pig-like animal native to the Western

Hemisphere. Other bones found were of an armadillo, a bear, a

porcupine and several other rodents. They were estimated to be

20,000 years old.

The discovery resulted in extensive media coverage and publicity. Hess decided to capitalize on his good fortune. He would charge admission for a tour of the cave, including the archaeological site.

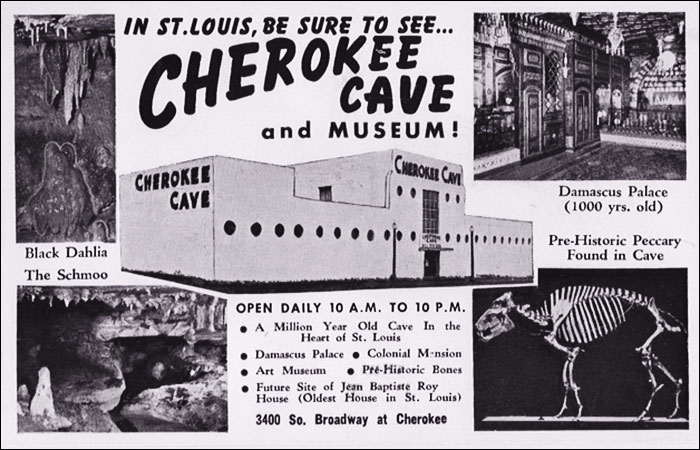

Hess converted the row houses he had acquired

on the DeMenil property into a museum. He reduced the height of the

residences, except for two in the center, filled the windows and

doors with bricks, and sprayed a heavy coating of cement over the

building to give it its shape. He painted the building white to

resemble the National History Museum in Mexico City.

Hess used the museum as the entrance to his cave by creating an opening in the cave's roof, underneath the museum. He built a series of concrete steps leading from the museum to the cave's floor, about 60 feet below street level. The interior of the cave was dynamited to increase height and enlarge passages. Hess branded his new venture the Cherokee Cave.

The Cherokee Cave was officially opened to the

public on February 22, 1950 ― Washington's birthday. As a promotion,

Hess admitted children, who were off school for the holiday, free of

charge. More than 200 children toured the cave, many of them lining up hours

before the doors opened.

Customers could enter and view exhibits in the

museum free of charge; Hess used it as a loss leader to entice

customers to pay an admission to tour his cave. The museum had multiple rooms and

there was something for everyone.

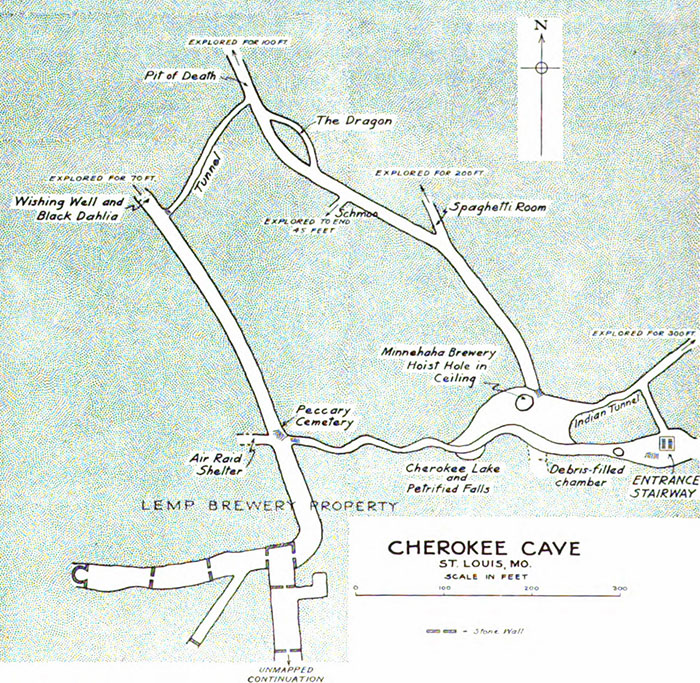

Admission to the cave itself was one dollar for

adults and fifty cents for children. A set of 25 steps descended

from the lobby down to a ramp, which led to a set of 47 steps, which

descended down into the cave.

The mile long tour

traversed two north-south corridors, connected by a natural passage

to the south. To keep from back-tracking, a man-made tunnel

connected the corridors at their northern ends.

From the foot of the stairway, the somewhat

sinuous southern passage led to the western of the two north-south

corridors. In this lowest part of the cave, a stream spilled noisily

into Cherokee Lake.

The Peccary Cemetery was at the junction of the

east-west passage and the western north-south corridor. It was a

deposit of vertebrate bones in a mixture of mud, sand, gravel and

fragments of limestone. It contained remains of armadillo, bear,

beaver, peccary, porcupine, raccoon, wolf and woodchuck.

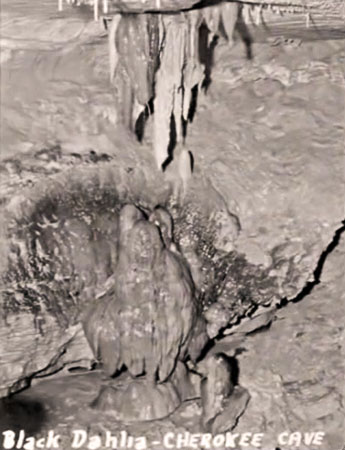

At the northern end of the western north-south

corridor was an unusual black and white onyx stalagmite. It was

discovered about the time of a much publicized murder case in Las

Angeles which the media had dubbed Black Dahlia. Hess capitalized on

the publicity and used the name for the stalagmite. Drip water from

the Black Dahlia fed a pool of water called the Wishing Well.

From the Wishing Well, the tour traversed the

man-made tunnel into the eastern north-south corridor. South of

their junction was the Dragon’s Den, an accessory lacteal passage

about 75 feet long. Here, Hess had installed a copper dragon with

red lightbulb eyes.

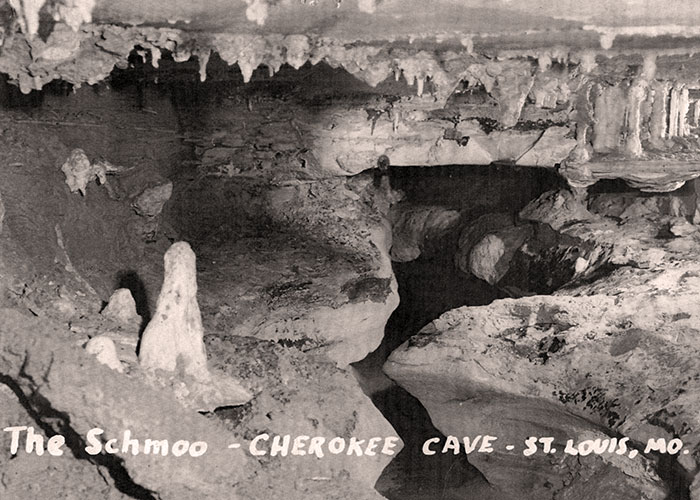

The Schmoo was a stalagmite named after Al

Capp's famous cartoon character. It could be viewed in a small

lateral cave opening about 50 feet south of the Dragon’s Den.

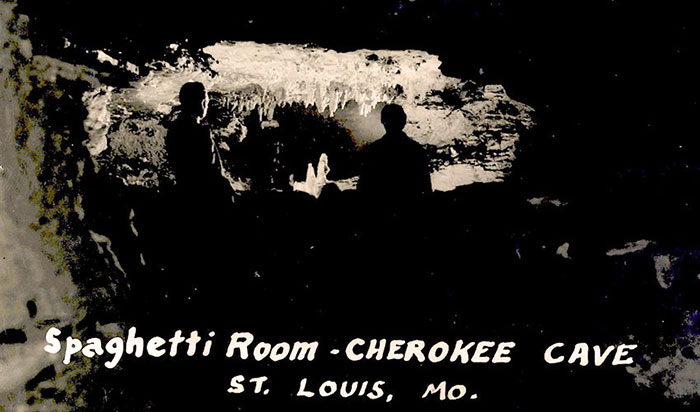

Another lateral channel, south of The Schmoo,

was the Spaghetti Room, so named because of the abundance of slender

stalactites hanging from the ceiling. The fill had not been

adequately removed for a visitor to enter.

The southern end of the eastern north-south corridor ended in the large room that the Minnehaha Brewery had used to store and age their beer. A hoist hole was visible in the ceiling.

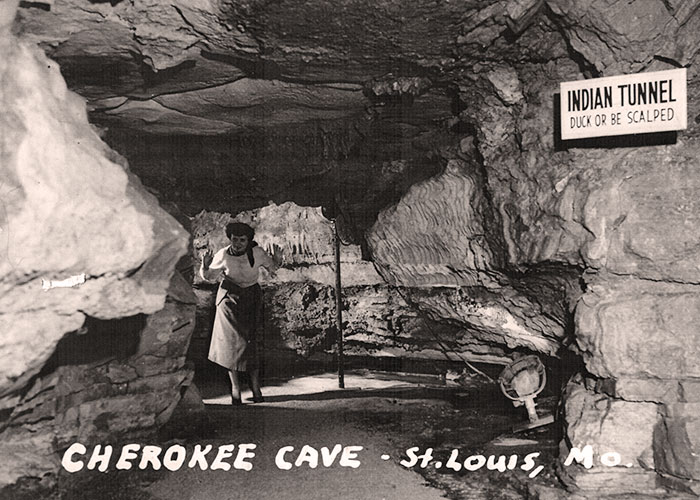

Indian Tunnel exited eastward from the brewery

room towards the Mississippi. It was the escape route for cave water

― and the escape route back to the entrance stairway.

In June of 1961, Lee Hess sold the Cherokee Cave, its entrance museum and the DeMenil Mansion to the Missouri Highway Department. The museum building was torn down and the cave sealed up to clear way for construction of the Ozark Expressway, now known as Interstate 55. The Highway Department had also planned to demolish the DeMenil Mansion, but modified their plans to allow the expressway to swing past the home. The Landmarks Association of St. Louis purchased the mansion and today operates it as a museum. Lee Hess died on July 20, 1961 after a two-year illness.

It is still possible to get into the Cherokee

Cave through an entrance in the old Lemp Brewery. Lemp had its own

cave system for storing and aging its beer which connected via

passages with the Minnehaha cave. The brewery’s current owner

occasionally allows accomplished spelunkers or personal friends to

enter. Lee Hess is no longer present to give guided tours.

Copyright © 2022 LostSTL.com |